- Welcome!

- #GivingTuesday

- Exhibitions and Events

- Past Exhibitions

- 2008: Antique Chinese Porcelains from Eight Dynasties (206 BCE to 1912)

- 2009: Will Barnet Prints / Gerson Leiber Watercolors

- 2010: Japanese Woodblock Prints from the Leiber Collection

- 2011: DRAWINGS DRAWINGS DRAWINGS: Recent Works on Paper by Gerson Leiber

- 2012-2013 Judith Leiber – An American Journey : From Artisan To Fashion Icon

- 2014-2015: THE MARRIAGE OF TRUE MINDS ~ GERSON AND JUDITH LEIBER

- 2016 Two Exhibitions: Gerson and Judith Leiber

- 2020 – The Garden of Friends

- Past Exhibitions

- Judith Leiber

- Gerson Leiber

- The Garden

- Press

- Tickets

- COVID-19

Judith Leiber Offers More Than ‘Mere Bagatelles,’ At The Jewish Center Of The Hamptons, June 2011

By Thomas McKee

|

| Evening bag legend Judith Leiber with biographer Jeffrey Sussman (Thomas McKee). |

East Hampton – From the average socialite’s perspective, artisan evening bag empress and CFDA Lifetime Achievement Award Winner Judith Leiber‘s high-gloss world suggests nothing short of poise, privilege, and meticulous materiality. Her 3,500 unique designs – from Fabergé-inspired egg minaudières to gold-plated teardrop châtelaines – have for more than half of a century been an icon of status and significance, now immortalized in the permanent collections of the Smithsonian, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and as of late, the privately-owned Leiber Museum and sculpture gardens, open for public viewing in Springs, East Hampton.Virtually every First Lady, from Mamie Eisenhower, to Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, to “dear friend” Barbara Bush and daughter-in-law Laura Bush, has toted a Leiber exclusive at every inaugural ball since 1953, and 1980s celebutante Pat Buckley coined the proverbial catchphrase – a Judith Leiber purse is “just big enough to accommodate a lipstick, a comb, and a one hundred dollar bill.”

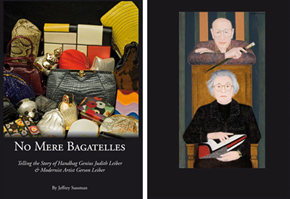

“Well, what more does the well-dressed woman require?” Leiber quipped in her biography, “No Mere Bagatelles,” penned by close friend and publicist, Jeffrey Sussman. The pair offered a public conversation and book signing this past Saturday, June 25, 2011, as a part of the Jewish Center of the Hamptons’ summer program of events.

But no matter how glamorous and well-studded with accolades her career might appear, no matter how revered her legacy is under the halogen lighting of department stores, inlaid in the crystal-encrusted clutches and Mondrian-inspired leather satchels exists tattered fragments of world-weary memories, and an impenetrable obstinacy to survive and succeed. Her oeuvre of artfully crafted evening bags serves as tactile proof that one finds purpose in passion.

|

| Judith Leiber Fabergé-inspired egg minaudière. (Courtesy Photo: PhillyMag.com) |

Leiber was born Judith Peto in Budapest, 1921. Her father was a prominent banker, who returned from international business trips with exquisite European purses as gifts for his wife, offering Judy the seeds of preliminary inspiration that would flower as she garnered her own aesthetic as the first female designer to join the Hungarian handbag-makers guild as a young woman. She began her collegiate education abroad in London, under her family’s urgings that she become a chemist, and pursue a career with a relative’s cosmetics company. However, as the grip of Nazism spread throughout Europe like a pitch-black shadow, she returned to her family in Budapest, refusing to leave their side despite their appeals.

“I had to learn a trade, so I learned how to make handbags,” she said at Saturday’s event, the crowd of listeners cooing in consensus. Under an apprenticeship at Pessl, a Jewish-owned handbag manufacturing company, Leiber honed her skills as a designer and pattern maker, learning firsthand every aspect of handbag construction, from design to completion. As Hitler’s troops ravaged Western Europe, and made their steady approach to the East, her fervor and passion for handbag design flourished – “it was the only bright spot in the darkness of a war-torn city,” Sussman writes.

When the Nazis occupied Budapest, and the Hungarian government conceded to the advance of the Third Reich, nearly 800,000 civilians were trapped in the flux of the siege. Two of Judith’s uncles were killed at the hands of Gestapo rifles for refusing to show their identity papers. Her father was abducted, and spent a harrowing series of weeks at Kispet, a work camp where he was forced to dig anti-tank trenches. However, good fortune and a family friend garnered the Liebers Swiss diplomatic immunity, and they were reunited in the basement of the Swiss legion in Budapest – the schutzpass is currently on display at the Holocaust Museum in Washington, DC. It was there, in a dingy cellar lined with mattresses for nearly 30 other people, that the Leibers waited out the devastation of the war, prisoners of their home city that swiftly crumbled around them, like a lifeless forest caught in a blaze.

The Soviet forces arrived in October of 1944 – “the lesser of two evils,” as described by Leiber, and artillery fire erupted throughout Budapest. “The whole city had become a charnel house and there were no funerals. The only ceremony for the dead was the crying, the wailing, and the barking of dogs – nothing was left but gaping holes like mouths without teeth.”

Leiber’s family, pushed to the precipice of starvation, was forced to eat the rotting meat of dead horse. She, her mother, and her sister helplessly witnessed the rape of an elderly woman at the hands of Soviet forces. Over 40,000 civilians were killed in the process. Russian soldiers and their Romanian allies raped more than 50,000 women, until the capturing of the capital in February of 1945.

The afternoon sunlight illuminated the room at the Jewish Center of the Hamptons, pouring yellow light onto the hushed crowd that listened with reverent silence to Leiber’s account of her experiences during the war. Beneath her serenely-stoic façade – the soft tufts of white hair, makeup-less skin that bore proudly the grooves of her 90 years, a white leather purse of her own design – one could see the suggestion of fatigue through her quiet eyes, an unwilling trepidation to access the reservoir of memory that lingers beneath the sequined purses that construct her success.

|

| Judith Leiber Mondrian-inspired envelope. (Courtesy Photo: Collector’s Weekly) |

“To those of us who lived through it, we did not need historians to tell us what happened. We shall carry our memories to our graves,” Sussman quotes.

Following the retreat of German forces, Leiber embarked on a life that would prove to sublimate the ugliness of a war-torn Budapest, for the beauty of handbags crafted through her own creative sensibility and inborn resiliency. In 1948, she married Gerson “Gus” Leiber, a small-town American G.I. and military radio operator. His smile captivated her from first sight, and their frequent trips to the opera and major museums throughout Western Europe offered Judith the sense of security that signaled the arrival of her soul mate.

“In 1945, an American G.I. was something magical and heroic. And that was Gus,” she said in her biography.

Gus was an archetypal dreamer, with aspirations to become an artist. He was an accomplished illustrator from a young age, and upon their arrival to the United States, he pursued study in the visual arts at the Art Student’s League, co-mingling with the upper echelon of modernists in the New York School and the Works Progress Administration. Throughout his career, he would produce a substantial body of work, experimenting in media from oil on canvas, illustration, and bronze-casted sculpture, all the while providing the unending support necessary for Judith’s revolutionary advances in the accessories industry. His works have been acquired by preeminent institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art, the National Gallery, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. On the surface, theirs is a classic American story of love and success, by route of Eastern Europe and World War II, the merit of two sets of working hands.

Evidenced by her biography, her appreciation and admiration of her husband’s talent and support is unending. However, when questioned on his influence over her design aesthetic, Leiber asserts, with a somewhat comical vehemence, that her creations are exclusively her own.

“He never influenced anything I made,” she said among the quiet laughter of the crowd, adding, “he was my critic, he told me if it was pretty, if he liked it or not.”

After rising through the ranks of the handbag industry, establishing a name for herself under clothier Nettie Rosenstein, creator of “the little black dress,” Judith started her own company in 1963. We know from author James Joyce that “mistakes are the portals of discovery,” and no maxim is more relevant when considering the inciting incident that catalyzed her success, and the very series of handbags that would come to epitomize her brand. Leiber recounted that she had ordered a shipment of metal evening bags, “known as minaudières” from an Italian company, who were to gold-plate the brass frames.

|

| Fans present vintage Leiber designs to the artist herself. (Thomas McKee) |

“After I noticed the first bag I unpacked was tarnished, I wondered what to do with it,” she said. “It was so unattractive that, for a moment, I thought it was useless. I certainly could not show it to anyone, so I decided to decorate the metal bag with crystals.”

According to Sussman, each minaudières consisted of 13,000 Swarovski crystals, and took five days to complete. The first encrusted clutch retailed for $150, but today, a Judith Leiber exclusive garners thousands of dollars from Sotheby’s to Christies, and every auction house in between. Over the course of the 30 years in which she was the sole designer and pattern-maker for her own brand, Leiber stretched the conception of what a handbag could be, creating molds of cats, seashells, hardbound books, mini-Buddha’s, penguins, and the iconic swan, showcased on the second season of “Sex and the City.” In 1994, she sold her company, yet her unparalleled craftsmanship and artistry has cemented her position among the most significant fashion legends of the 21st century, and people continue to collect her designs as if they were masterworks of a contemporary modernist. Her biography, “No Mere Bagatelles,” is a bona-fide summer read, worthy of further exploration.

Judith Leiber has led a life saturated by the wisdom of experience, from entrepreneurial fervor, to the resiliency of the human condition. Despite a recent stroke, her stature continues to possess the strength of a tested woman, unafraid of the passage of time, possessing tangible proof of a life of prolific creativity and determination. Although she claims to be currently without a creative outlet, she seems resigned to the respectful stillness of her later years, enjoying the stories of visitors and passers-by that frequent the galleries of the Leiber Museum and gardens.

“I don’t do anything,” she said through a half smile. “I read books, hang around, and swim laps every morning.”

The Leiber Museum is located at 446 Old Stone Highway, East Hampton, and is open to the public seasonally, every Saturday and Sunday from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. Currently on view in the galleries are over 150 Judith Leiber handbags, the oil paintings and illustrations of Gerson Leiber, and over 140 pieces of antique Chinese porcelain, personally collected by the couple over the course of 20 years.

Jeffrey Sussman is the author of 10 non-fiction books, two novels, dozens of short stories, book reviews, and numerous articles on a wide variety of topics. In addition, he wrote and produced two television series. He is the president of Jeffrey Sussman, Inc., (www.powerpublicity.com), and marketing and PR firm based in New York City. His email address is marketingpro@aol.com.

The Jewish Center of the Hamptons is located at 44 Woods Lane, East Hampton. For more information of their summer program of events, go to www.jcoh.org, or call 631-324-9858.

Press

- Back To The Garden - Portray Magazine

- FIU News – Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU to launch Judith Leiber: Master Craftsman

- Christie’s – The best museums for handbag collectors

- Long Island Weekly – New Nassau County Museum of Art Exhibition Highlights All Four Seasons

- Newsday – ‘The Seasons’ is in full bloom at Nassau County Museum of Art

- Obituaries

- New York Post - The WWII love story behind NYC’s sparkliest handbags

- New York Magazine - Hillary Clinton and Sex and the City Loved These Rhinestone Purses

- WAG Magazine - Celebrating the Creativity of Judith Leiber

- Dexigner - Judith Leiber: Crafting a New York Story

- East Hampton Star - Leiber Handbags Celebrated at the Museum of Arts and Design

- Hadassah Magazine - Judith Leiber: All in the Bag

- Couture Notebook, "Judith Leiber: Crafting a New York Story” with Crystal Minaudières

Biography

NO MERE BAGATELLES, the story of Holocaust survivor and handbag design genius Judith Leiber and modernist artist Gerson Leiber, has just been published. Read more here.

Search